A Weekend in Chandigarh

Words and photos by Gerald Jason Cruz.

I took a weekend trip from Mumbai to the City Beautiful– the one nestled amongst the foothills of the Himalayas and sprawling like an open hand beyond its original bounds. Chandigarh, a union territory serving as the capital of both the states of Punjab and Haryana, is relatively unknown to non Indians with one notable exception: architects. For the latter, it is an important site as one of the few fully planned cities embodying the principles of the modernist movement. And for that honor, it earned its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016. I certainly visited the city for this reason, intending to make a pilgrimage to the renowned Capital Complex. But after spending a few days here, I ended up leaving with a different perspective. One that challenges the legacy of architects and examines the allure of the planned city (and, of course, not forgetting to eat really good food too).

The Capital Complex and Le Corbusier

They say to never meet your heroes, but when one arrives in Chandigarh, who exactly are you meeting? The answer, at face value, is the infamous Le Corbusier, lesser known as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret. Le Corbusier had already been practicing for over forty years before being selected to design key buildings for a new planned city in India in the late 1940s. I say “design key buildings” because Chandigarh as a concept existed before he was brought onto the project. After already propelling concrete as a utilitarian material of the future and gaining worldwide architectural fame, what made Chandigarh special was it was a culmination of Le Corbusier’s years of experience and architectural philosophy. Here was a blank slate: a vast swath of farm land, a large budget to work with, for an audience that looked up to him, for a province recently split in two and for a country in search of an identity. And in a way it was Le Corbusier in his purest, most unapologetic self. There was no need to prove himself, and there was almost free reign to design as he saw fit.

The entrance of the High Court of Punjab and Haryana.

The entrance of the High Court of Punjab and Haryana.

When one enters the Capital Complex, one enters an architectural sanctuary closed off to the rest of the city. While there have been many reviews on the architecture of the complex, what I noticed in particular was how the monumental and imposing structures Corb designed actively try to fight the passage of time. How can something as immortal and immovable as raw concrete evolve? The stories they tell are seen in the subtle interventions throughout the site over its seventy year history. The utilitarian slab of concrete at the center of the site, once originally serving as a parking lot, is now an empty expanse absorbing the humidity and heat of the summer. The Open Hand monument, along with other designed spaces for the public and expression are now closed off by barbed wires and patrolled by armed forces due to security concerns. The sweeping facades of buildings, with their béton brut surfaces give way to hastily installed CCTV cameras, air conditioning units, and satellite dishes. Ponds and channels once designed to hold water to reflect the buildings beneath them are shallow, drained, and in need of repair. Outdoor stairs and ramps designed to serve as communal paths are devoid of people. All of these things seemed out of place.

Paradoxically however, it made sense, for the entire concept of the Capital Complex was in itself out of place. Le Corbusier had made no serious effort to adapt the architecture he created to the foothills of the Himalayas. The result is a transplanted philosophy, an architecture that is Indian only because it exists in India. An architecture that had its ideals and functions cemented in place since its foundations were poured. So in the moment when the state of Haryana eventually separated from Punjab, and both states wanted to retain Chandigarh as their capital, the entire functionality that Le Corb had envisioned for the Capital Complex broke down. And for that reason, we cannot blame the desires and needs of the people to destroy his vision for the sake of making it usable. Le Corbusier’s ego lost the battle with time, and we’re now left with the concrete shells wanting to stay frozen, but having to accept time’s passage.

Foreground: The Palace of Assembly. Background: The Secretariat Building.

Foreground: The Palace of Assembly. Background: The Secretariat Building.

The Overlooked Contributors

Nestled in between the midrise government buildings of Sector 19 is a more modest bungalow which served as the architecture and engineering offices for the planning of the city. Today it is the Le Corbusier Centre, which houses models, photos, and archives of documents pertaining to the planning of Chandigarh. It is here where you get to meet the others who worked under and alongside the man who got all the attention. Apart from the dozens of Indian architects, draftsmen, and engineers lost to time for all but a photograph hung in the exhibition, there are three other key figures overlooked in the project: Maxwell Fry, Jane Drew, and Pierre Jeanneret (notably, Le Corbusier’s cousin). It was these three who oversaw the design of other key infrastructure of the city, including all housing typologies, educational and cultural institutions, as well furniture for many of these buildings. These aspects were certainly less flashy than the Capital Complex, but were more influential in shaping the way that residents actually lived their lives.

The other designers were not without their faults either, though. In an attempt to impose a more modern way of living, the new housing typologies had less regard for the way of life that Punjabis were used to. This resulted in complaints and makeshift solutions, especially from the first few residents. And in a desire for efficiency and practicality, concrete was a particularly used material: from shelves built into the walls of bedrooms, to screens and brise soleils that reduce sunlight exposure and let in wind. However, the permanence of these elements resulted in a lack of flexibility as fixtures could not be changed or moved, and the heritage status of many of these buildings disallow retrofits to be made to align with more modern housing needs.

Exhibition at the Le Corbusier Centre.

Exhibition at the Le Corbusier Centre.

Chandigarh Today: A City of Contrasts

The ultimate spirit of Chandigarh is its ideals as a planned city– a chance to start anew for the recently split province of Punjab, and for the newly independent India. It wants to push the boundaries to create a utopia. Originally dreamt up by architects Albert Mayer and Matthew Nowicki, Le Corbusier reworked the original plan to be more in line with his urbanist philosophy. The result is a relatively ordered grid of superblocks, designed to be self-sustaining with busy avenues connecting them. These superblocks, numbered as Sectors from 1 to 50 and beyond, were then assigned different functions akin to the human body. Administrative (the head), education and culture (the hands), greenspace and parks (the lungs), commercial and entertainment (the heart). Planning was important at the early stages of the city’s development because it had to entice people to move there. In a way, it worked– Chandigarh today is a thriving city of over one million people and has one of the highest quality of life measurements in India. It has ample green space and is clean and orderly, attracting many to move there.

However, a lot of these decisions had unintended consequences. Since all sectors continued in rows southwest from Sector 1 (the Capital Complex), the closer you were to the administrative center, the more well off and important you were. The numbering of each sector ended up being used by residents to determine class and status. Chandigarh is also more car dependent compared to other cities in India. Its train station is located on the fringes of the territory surrounded by forests, and we relied on taxis and autos to get around anywhere. Despite the union territory being a planned city, its urban growth has extended beyond its original bounds, with the superblock scheme continuing south into the city of Mohali in Punjab, and a new planned city built to the east, Panchkula in the state of Haryana. The latter is more akin to the original layout that Mayer and Nowicki had envisioned. The exclusivity and prestige of living in and around Chandigarh merely created a real estate craze, as land prices skyrocketed due to the perceptions of the city. It was clean, new, designed by a famed architect, the future of living, and so on. Which begs the question: who is Chandigarh really for, today? And more importantly, what does this experiment teach us about planned cities, and how they evolve over time?

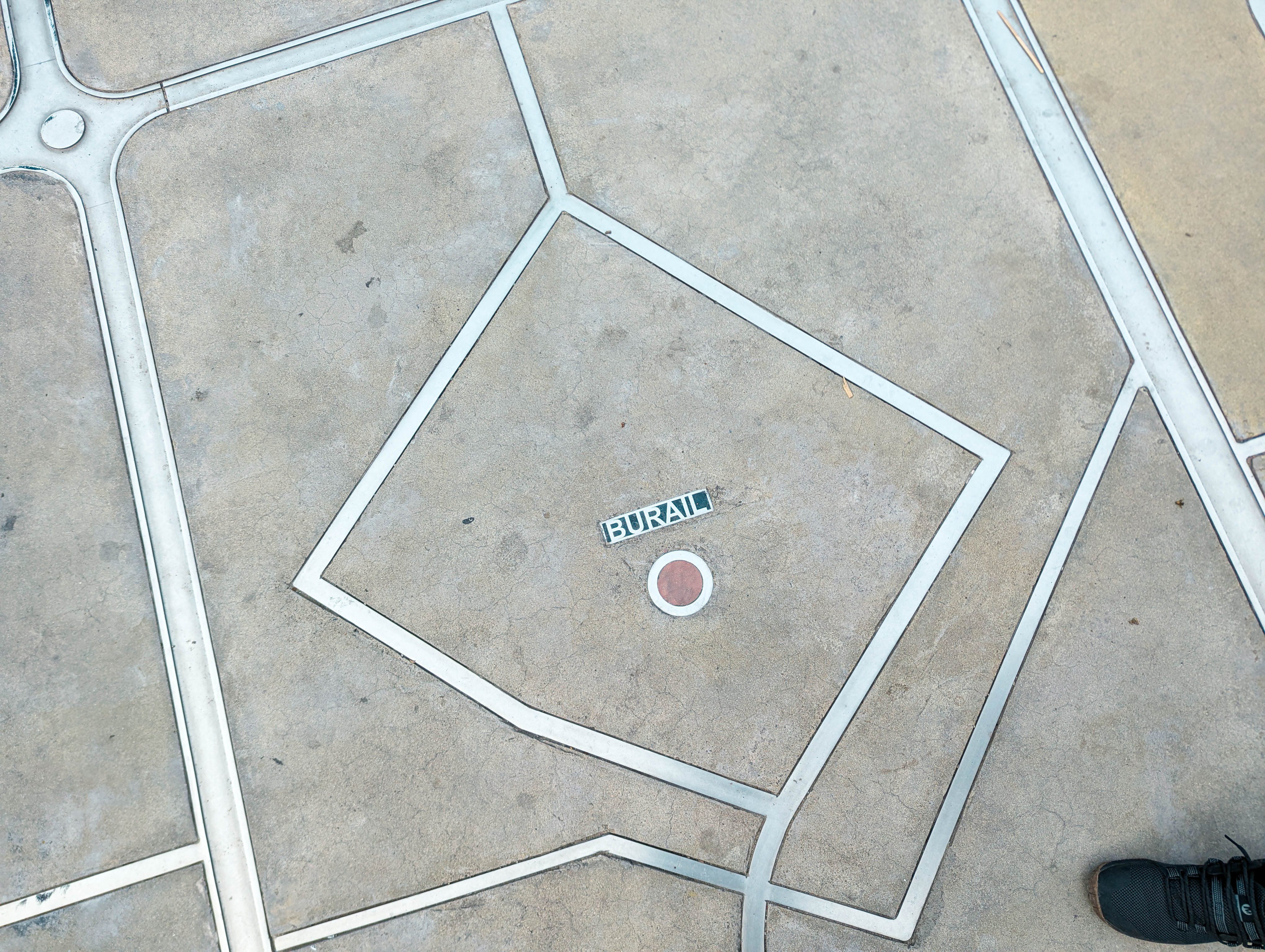

The footprint of Burail within the superblock of Sector 45, as seen in the Map of Chandigarh at Sector 17.

The footprint of Burail within the superblock of Sector 45, as seen in the Map of Chandigarh at Sector 17.

There’s one more oddity in Chandigarh that I’d like to point out. At the center of Sector 45 is an area that doesn’t quite fit in with the rest of the ordered grid. A square area perpendicular to the north, merely cut off by the wide superblock avenue in its southeast sticks out like a sore thumb. The roads inside are not straight lines but weave organically between non-rectangular buildings. This oddity is Burail, one of the dozens of villages that existed in the pre-Chandigarh landscape. It is one of the only settlements that escaped Corb’s utopian vision, and provides us a glimpse into how life may have developed in the absence of the plan, or rather, in spite of his plan. It is a thriving and tight-knit urban village that houses industries not available in the rest of the city. It is also a scar that serves a reminder of the reality of planned cities: they erase the history of the places that came before them in the pursuit of a “better” future.

Burail was brought to my attention by one of my colleagues in Mumbai before travelling to Chandigarh, as a pocket of intrigue within the strict order of the city. When asked about visiting Burail during our trip there, our tour guide (a Chandigarh local who lived within the Sector 40 area) remarked that there was nothing to see there and described it as a “prison”. I think this is telling of the way that residents view oddities like Burail: because it goes against that overarching vision of what Chandigarh is supposed to stand for, it is a flaw. This is despite the fact that Burail has been inhabited for over three hundred years before the concept of Chandigarh ever broke ground. The contrast between the ideal and reality of how people live is one that only shows up over time. Burail serves as an interesting case study for how a natural urban typology forms when the planning of authorities fails to keep up. If the village never gained its autonomy from the rest of the Chandigarh plan, its fate would be sealed like the other villages that were bulldozed for the sake of progress.

The Open Hand Monument, a now enduring symbol of Chandigarh.

The Open Hand Monument, a now enduring symbol of Chandigarh.

My Conclusions

At the end of the trip, I left Chandigarh with a different perspective on Le Corbusier. Something like the Capital Complex would never exist today. I make that conclusion because there will never again be a complex dreamed up by a single person. Nowadays, there are too many stakeholders for there to be a mythos of a single person behind a plan. This may have been us learning from our mistakes, and we realized that entrusting the design of an entire civic project to a single person handed them too much control. Maybe, there are just too many architects today for there to be reverence for a single figure. The complex for all its criticisms preserves this moment of architectural history– a time of idealism, experimentation, and exaltation. It is therefore Corb’s greatest legacy, and it shows the failures of planning for the future, or at least that his ideals didn’t exactly translate into that future. It is a poignant reminder of the power of design and the built environment.

As for the city, will there ever be another Chandigarh? The answer is yes, there will. For as long as there is a desire for something new, flashy, and better than the urban spaces we live in today, the idea of a planned city stays alive. The allure of the planned city is so infectious, that one only has to look west across the Arabian Sea in order to see its next iterations (where superblock grids have transitioned into linear lines). It’s a story that continues to repeat itself: the idea that we have to reinvent the way we live, and that these grand ideas for architecture and urban planning will be the solution to our problems. While there is some truth to that, the reflections of Chandigarh’s development over the decades of its existence have shown how we look back on these ideas of the future and how the people who end up living there actually interact with what’s there. It is an experiment that concludes that planning at this scale is too grand and too rigid, and that we must prioritize adaptability over perfection. As much as designers try to fight it, human needs will always evolve beyond what we can predict, so let’s give the space for that adaptability and change.

This essay was inspired by and references details from the book “Chandigarh: The Backstory - And The City It Couldn’t Be” by Vibhor Mohan. I recommend reading it if you’d like to learn more about the planned city beyond the buildings of Le Corbusier.